Amherst police chief finalists stress anti-racism cred, discuss other issues in separate meetings with public

AMHERST — Both Chelmsford Police Lt. Todd Ahern and Amherst interim Police Chief Gabriel Ting are citing their lived experiences, as well as their significant service to public safety, as reasons they should become the next police chief of the Amherst...

Smart search shirt: AHRS invention group’s garment will report rescuers’ vital signs and location

AMHERST — Often during search-and-rescue efforts, emergency personnel in the field prioritize helping those lost, trapped or otherwise in trouble, rather than focusing on their own safety and well-being.Understanding the risks they take, a group...

Most Read

Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

As Hadley works on energy storage bylaw, some question why the town has to allow them at all

As Hadley works on energy storage bylaw, some question why the town has to allow them at all

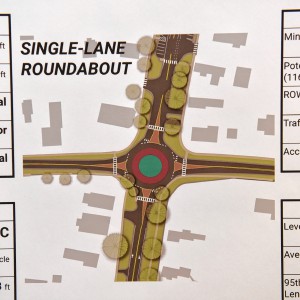

Residents seek to balance intersection upgrades with preservation of Sunderland character

Residents seek to balance intersection upgrades with preservation of Sunderland character

Don Michak: Dig deeper after scandalous court ruling in Soldiers' Home case

Don Michak: Dig deeper after scandalous court ruling in Soldiers' Home case

Susan Tracy: Support Ukraine funding

Susan Tracy: Support Ukraine funding

Amherst police chief finalists stress anti-racism cred, discuss other issues in separate meetings with public

Amherst police chief finalists stress anti-racism cred, discuss other issues in separate meetings with public

Editors Picks

Defying the odds: Hadley’s Owen Earle back competing less than two years removed from horrific accident

Defying the odds: Hadley’s Owen Earle back competing less than two years removed from horrific accident

UMass trustees OK 2.5% tuition increase

UMass trustees OK 2.5% tuition increase

Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

Jena Schwartz: Things I have not said

Richard S. Bogartz: What the ghosts of Warsaw Ghetto know

Richard S. Bogartz: What the ghosts of Warsaw Ghetto know

Sports

Guest columnist Karen List: A legend made in Iowa

The thousands of women who played high school basketball in Iowa over the years look at the adulation surrounding University of Iowa star Caitlin Clark and think: “That’s about right.”Clark, as you probably know, is the NCAA Division 1 all-time...

Opinion

Guest columnist Dr. David Gottsegen: Age issue not so key as question of marbles

A poll published in The New York Times on Sunday, March 3, found that nearly half of voters now strongly agree that Joe Biden is “too old” to be president, more than twice the number of voters who strongly agree that Donald Trump is “too old.” People...

Guest columnist Ali Wicks-Lim: Racism is in our way

Guest columnist Ali Wicks-Lim: Racism is in our way

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Halfway there — 2023 a year for major green projects in Amherst

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Halfway there — 2023 a year for major green projects in Amherst

Jeff Lee: Amherst needs info before raising Jones borrowing cap

Jeff Lee: Amherst needs info before raising Jones borrowing cap

Arts & Life

Preserving a key part of Emily Dickinson’s legacy: Historic Evergreens house reopens at the Emily Dickinson Museum

Between the “Dickinson” series on Apple TV+ and movies such as 2016’s “A Quiet Passion,” interest in Emily Dickinson has grown in the last several years, even beyond the already intense admiration that existed for her poetry among readers and literary...

Amherst council approves mandatory rental inspection program

Amherst council approves mandatory rental inspection program

Amherst officials cool to bid to double spending hike for regional schools

Amherst officials cool to bid to double spending hike for regional schools

One upon a story slam: This year’s Valley Voices winners head to a final competition

One upon a story slam: This year’s Valley Voices winners head to a final competition

Police investigating bullets striking homes in Belchertown

Police investigating bullets striking homes in Belchertown

Water rate hike eyed to fund new tanks in Hadley

Water rate hike eyed to fund new tanks in Hadley

Three vying for two Hadley Select Board seats in sole contested race

Three vying for two Hadley Select Board seats in sole contested race

In federal lawsuit, teacher accuses Amherst schools of violating civil rights, other district policies

In federal lawsuit, teacher accuses Amherst schools of violating civil rights, other district policies

The Lehrer Report: April 12, 2024

The Lehrer Report: April 12, 2024

UMass basketball: Josh Cohen, Robert Davis Jr. first Minutemen to enter transfer portal

UMass basketball: Josh Cohen, Robert Davis Jr. first Minutemen to enter transfer portal UMass confirms sports programs moving to the Mid-American Conference as it becomes 13th member

UMass confirms sports programs moving to the Mid-American Conference as it becomes 13th member Amherst College women’s basketball coach Gromacki fastest in NCAA history to reach 600 wins

Amherst College women’s basketball coach Gromacki fastest in NCAA history to reach 600 wins UMass basketball: Matt Cross leads balanced Minutemen past Saint Louis for first A-10 road wi

UMass basketball: Matt Cross leads balanced Minutemen past Saint Louis for first A-10 road wi Guest columnist Martha Hanner: Spirit of philanthropy can uplift so many others

Guest columnist Martha Hanner: Spirit of philanthropy can uplift so many others The Beat Goes On: Chamber music at The Drake, a Saint Patrick’s weekend musical smorgasbord, and more

The Beat Goes On: Chamber music at The Drake, a Saint Patrick’s weekend musical smorgasbord, and more Speaker for the whales: Indigenous artist interprets endangered right whale’s legacy and meaning

Speaker for the whales: Indigenous artist interprets endangered right whale’s legacy and meaning The ABCs of children’s books: ‘Alphabet Soup’ at the Eric Carle Museum looks at how picture books come to life

The ABCs of children’s books: ‘Alphabet Soup’ at the Eric Carle Museum looks at how picture books come to life Crossing borders: Hadley author’s short story collection explores the human stories behind immigration

Crossing borders: Hadley author’s short story collection explores the human stories behind immigration