A dream fulfilled: Aaron Lansky, whose Yiddish Book Center helped reclaim a culture, stepping aside

| Published: 03-14-2024 2:43 PM |

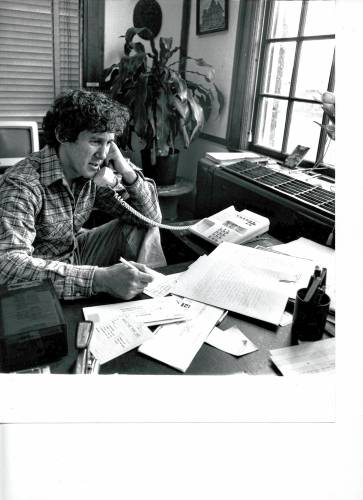

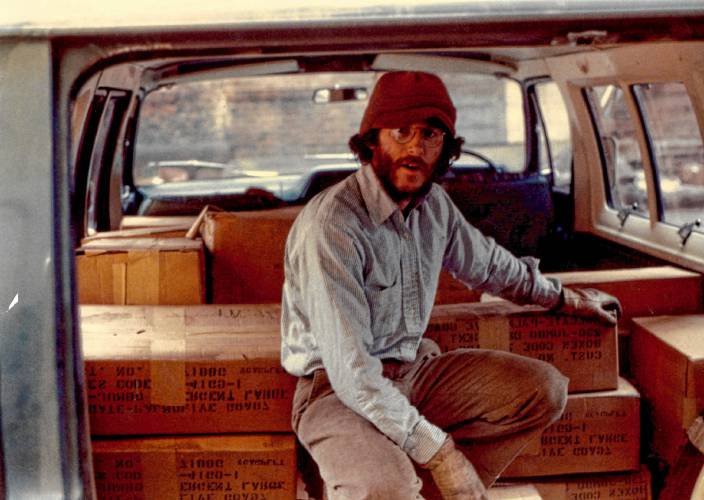

AMHERST — Aaron Lansky, founder and president of the Yiddish Book Center, began his 2004 memoir about his work, “Outwitting History,” with a memorable anecdote: how he’d taken a dead-of-night train from the Valley to Manhattan in 1980 and, with the help of a number of friends, rescued some 5,000 Yiddish books from a mammoth dumpster, working through a steady rain and pooling just enough money to rent a U-Haul truck to bring the books back to Massachusetts.

Yet Lansky, who at that time had taken a leave of absence from a graduate program in Eastern European studies to try and preserve Yiddish books, was left wondering if what he was doing was some kind of nostalgia trip, a quixotic quest with little chance of success.

Forty-four years later, those questions have been long been put to rest. The Amherst book center has now preserved some 1.5 million Yiddish books, after Lansky had been told at the outset of his work that there were likely no more than 70,000 such titles in existence — or recoverable — worldwide.

Meantime, the book center has become one of the largest Jewish cultural organizations in the world, with varied education programs, an oral history project profiling Yiddish speakers from around the world, exhibits and special programming, and a growing digital library of Yiddish books that can be accessed by anyone.

So Lansky, who’s 68, has decided to wind down his time with the center and turn the leadership reins over to a longtime colleague. He’ll retire from the center in June 2025, and Executive Director Susan Bronson, who’s been with the center since 2010, will become president.

Lansky, who with his wife, Gail, moved from the Valley to Stockbridge a couple years ago, said he’ll continue to have a role with the center for a few years afterward as a senior adviser.

“I guess they’re calling it ‘senior adviser’ to rub salt in the wound a bit about my age,” he said with a laugh during a recent phone call from his home.

On a more serious note, he said announcing his retirement now was simply about “putting the word out about the change. There was no ‘a-ha’ moment. It’s just the right time to make the transition.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Granby Bow and Gun Club says stray bullets that hit homes in Belchertown did not come from its range

Granby Bow and Gun Club says stray bullets that hit homes in Belchertown did not come from its range

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

‘Home away from home’: North Amherst Library officially dedicated, as anonymous donor of $1.7M revealed

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Super defers Amherst middle school principal pick to successor; one finalist says decision is retaliation for lawsuit

Back to the screen: Amherst authors’ popular ‘Spiderwick Chronicles’ gets a new streaming adaptation

Back to the screen: Amherst authors’ popular ‘Spiderwick Chronicles’ gets a new streaming adaptation

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Annette Pfannebecker: Vote yes for Shores Ness and for Deerfield

Sole over-budget bid could doom Jones Library expansion project

Sole over-budget bid could doom Jones Library expansion project

“I’m still full of beans,” he said. “But I’d like to have more time for study and reading, and I’d like to do some teaching.”

He also praised Bronson for the initiatives she’s developed at the book center, such as the annual summer music festival, Yidstock, and reading programs in Yiddish literature, featuring the work of revered writers such as Sholem Aleichem and I.L. Peretz, that are brought to public libraries.

“I’ve had a close and cordial relationship with Susan for 14 years,” Lansky said. “She’s a real professional with great ideas and leadership.”

In a statement, Bronson said, “I am humbled and excited to lead the Yiddish Book Center into its next chapter. Aaron’s legacy is profound, and I am committed to building upon his work.”

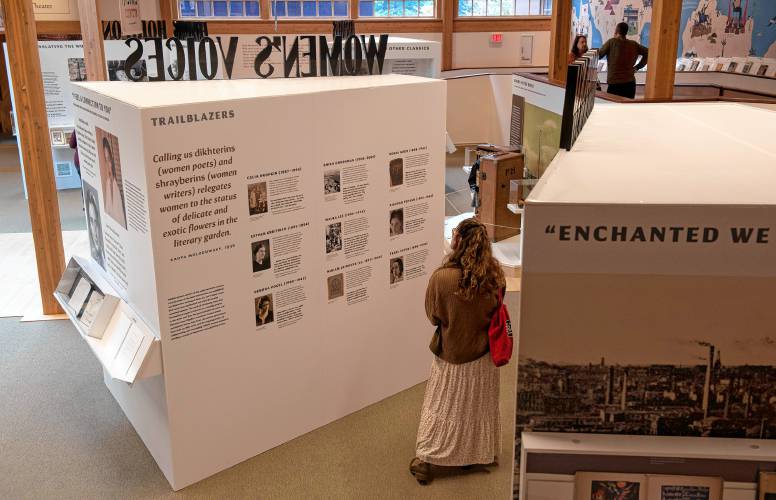

Bronson and another staff member, David Mazower, the book center’s research bibliographer and editorial director, also played key roles in developing the center’s new exhibit, “Yiddish: A Global Culture,” an expansive project that opened last fall, and which explores Yiddish literature, theater, music and more that flourished from the late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century in several parts of the world, especially in Eastern Europe.

As much as anything, Lansky says, that exhibit helps dramatize the idea he first developed as he began collecting books over four decades ago. As he met with Yiddish speakers and their descendants across the country and heard their stories, he came to realize that he was doing more than saving aging books.

“There was a whole culture, a whole world and history, that was at risk of disappearing,” he said. “That was something that was so important to preserve.”

Born in New Bedford, Lansky heard his grandparents, and to some extent his parents, speaking Yiddish when he was growing up, but he didn’t begin learning the language himself until he was an undergraduate at Hampshire College in the mid 1970s.

Trying to expand his studies then, and again later as a graduate student at McGill University in Montreal, he discovered there was a dearth of materials and courses available in Yiddish literature, which set him on his journey to collecting Yiddish books.

He notes that there was also a bias against, or disinterest in, Yiddish at the time. Given the murder of so many Yiddish speakers in the Holocaust, and the assimilation of former Yiddish speakers in countries such as the U.S., “a lot of people, including most Jewish leaders, just assumed Yiddish was on the way out,” he said.

But his efforts at collecting Yiddish books proved so successful that by 1997, the book center had opened on the Hampshire College campus, the outside modeled on an East European shtetl.

Lansky said he and staff envisioned making education a part of the center early on: “We didn’t intend just to be a book depository,” he explained.

But other changes and additions to the center “have been more of an organic progression, things that only became really clear in retrospect.”

He’s particularly excited about a program, expected to be completed next year, in which the book center has partnered with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City, the New York Public Library, and the National Library of Israel to collectively digitize their Yiddish collections, allowing people to call up a whole book by searching by title or author.

And looking back, Lansky says he feels blessed to have had the chance to turn what might once have seemed like a wild goose chase into a permanent home for Yiddish writing, culture and education.

“When all is said and done,” he said in statement, “I was able to act on my dreams, save a literature, and reclaim a culture, and that, I think, makes me one of the world’s luckiest people.”

Sharing a few notes: High schoolers coaching younger string players one on one

Sharing a few notes: High schoolers coaching younger string players one on one Reyes takes helm of UMass flagship amid pro-Palestinian protests

Reyes takes helm of UMass flagship amid pro-Palestinian protests Amherst poised to hire police department veteran as new chief

Amherst poised to hire police department veteran as new chief